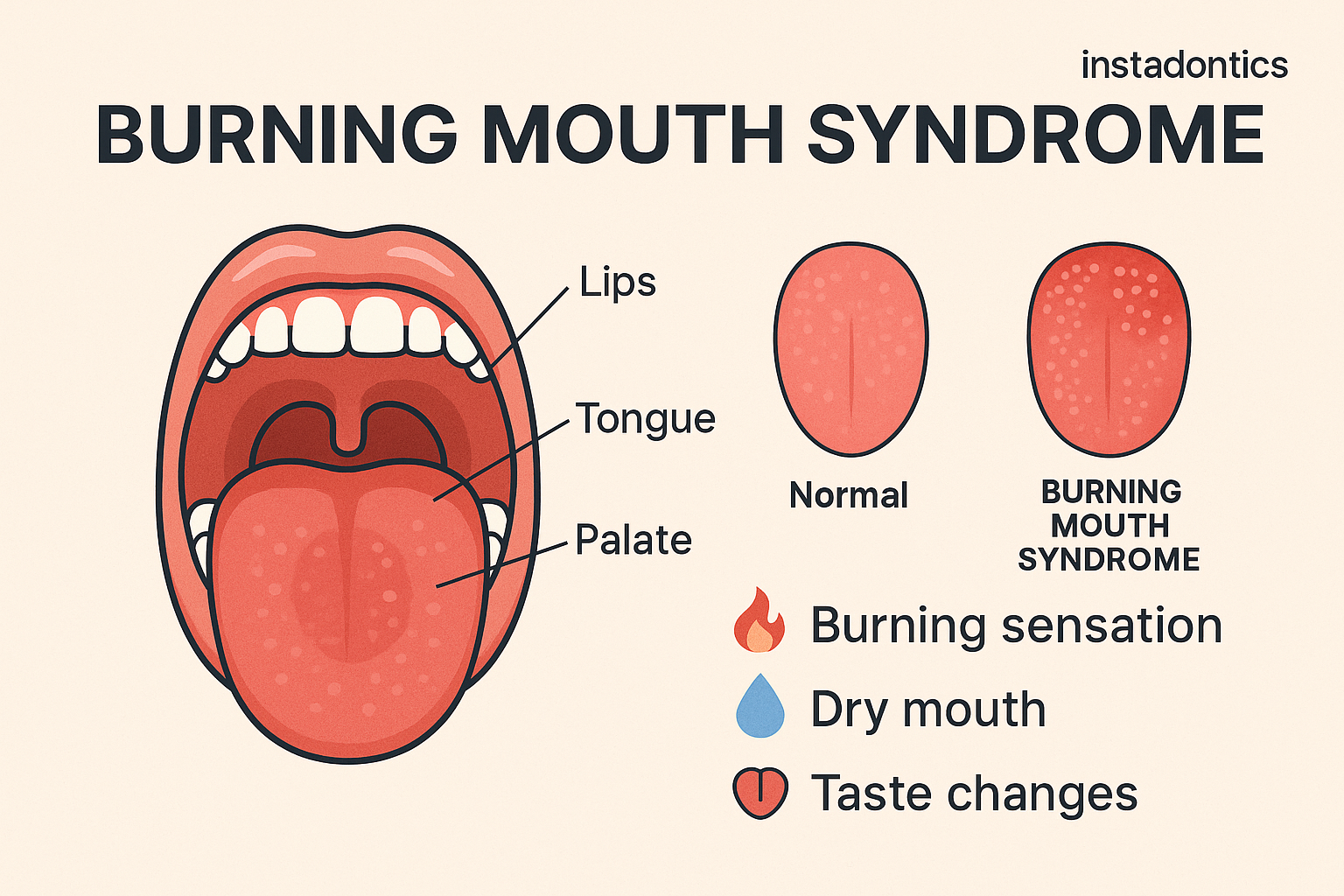

Burning Mouth Syndrome Causes, Risk Factors, and Clinical Insights | Burning Mouth Syndrome (BMS) is a perplexing and often distressing oral condition characterized by a persistent burning sensation in the mouth without an identifiable medical or dental cause. It affects the tongue, lips, roof of the mouth, gums, or widespread areas of the oral cavity. While it can affect individuals of all ages, it is most commonly reported in postmenopausal women and individuals over the age of 50. The condition is chronic, often fluctuating in intensity, and may be associated with other oral symptoms such as dryness, altered taste (dysgeusia), or tingling.

This article provides a detailed exploration of the underlying causes of BMS, classifying them into primary (idiopathic) and secondary (underlying condition-related) categories. It also addresses risk factors, diagnostic challenges, and emerging research directions, offering both patients and clinicians a comprehensive understanding of this elusive syndrome.

What is Burning Mouth Syndrome?

Burning Mouth Syndrome refers to the chronic sensation of oral burning or discomfort that persists for months, typically without any visible clinical lesions or abnormalities. It can occur daily and may worsen as the day progresses. BMS is often idiopathic, meaning it occurs without a known cause, but may also be linked to systemic, local, or psychological factors.

Typical symptoms include:

- A scalding or burning feeling, most often on the tongue

- Dry mouth or increased thirst (xerostomia)

- Bitter or metallic taste

- Numbness or tingling

- Discomfort that intensifies with stress, fatigue, or after speaking or eating

For many, these symptoms are not just physically uncomfortable but can significantly impact daily life, self-esteem, eating habits, and mental well-being.

Classification: Primary vs. Secondary BMS

Burning Mouth Syndrome is generally classified into two types:

1. Primary (Idiopathic) BMS:

No identifiable medical or dental cause. It is considered a neuropathic condition related to damage or dysfunction of the nerves involved in pain and taste.

2. Secondary BMS:

Caused by underlying medical conditions or factors such as nutritional deficiencies, hormonal changes, dry mouth, or allergic reactions. In these cases, treating the underlying cause can relieve symptoms.

Neuropathic Mechanisms in Primary BMS

Emerging research suggests that primary BMS may stem from alterations in the peripheral or central nervous system. Studies have found abnormalities in small-diameter sensory nerve fibers responsible for pain and thermal sensation.

Patients with primary BMS often show signs of:

- Peripheral nerve damage: especially involving the trigeminal nerve

- Central sensitization: altered brain response to oral stimuli

- Taste dysfunction: such as hypogeusia (reduced taste), which can interfere with pain regulation

These changes contribute to a hypersensitive oral mucosa, meaning normal stimuli such as talking or eating can trigger burning sensations.

Burning Mouth Syndrome Causes of Secondary BMS

Secondary causes of Burning Mouth Syndrome are diverse and can be grouped into systemic, local, and psychological categories:

1. Nutritional Deficiencies

Deficiencies in essential nutrients can lead to changes in the oral mucosa and nerve function, directly contributing to the symptoms of Burning Mouth Syndrome. These nutrients play critical roles in maintaining the integrity of the nervous system and the overall health of the oral cavity. When lacking, they may lead to symptoms such as glossitis, mouth soreness, and a burning sensation.

- Vitamin B12 deficiency: This vitamin is crucial for nerve function and red blood cell production. A deficiency can lead to nerve damage, which manifests as tingling, numbness, or a burning sensation in the mouth. Patients may also experience fatigue, pallor, and cognitive difficulties. B12 deficiency is common in individuals with malabsorption syndromes, vegans, or those taking certain medications like metformin or proton pump inhibitors.

- Iron deficiency anemia: Iron is necessary for oxygen transport and immune function. Anemia due to iron deficiency can cause mucosal atrophy (thinning of the mouth lining), reduced oxygenation of tissues, and increased susceptibility to infections, all of which may present as burning mouth symptoms. Patients may also exhibit fatigue, brittle nails, or pica (cravings for non-food substances).

- Folic acid deficiency: This B-vitamin is essential for DNA synthesis and repair. When deficient, patients may experience soreness of the tongue, ulcers in the mouth, and burning sensations. Folic acid deficiency often coexists with other deficiencies and is more common in individuals with poor diets, alcohol dependency, or gastrointestinal absorption issues.

Addressing these nutritional deficiencies through dietary improvements or supplementation can often resolve symptoms. Blood tests are used to identify specific deficiencies, and treatments may include oral supplements or, in more severe cases, intramuscular injections.

2. Hormonal Changes

Most prevalent in postmenopausal women, BMS has been linked to fluctuations or reductions in estrogen, which can affect salivary gland function and oral mucosal sensitivity.

3. Dry Mouth (Xerostomia)

Reduced salivary flow, whether from medications, autoimmune conditions (e.g., Sjogren’s syndrome), or aging, contributes to oral discomfort and burning.

4. Oral Candidiasis

Though often asymptomatic, subclinical fungal infections can provoke sensations of burning and irritation in the mouth.

5. Allergic Reactions or Irritants

Contact allergies to dental materials, oral hygiene products, preservatives, or flavoring agents can cause BMS-like symptoms.

6. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Acid reflux can lead to a burning sensation in the throat and mouth, especially when acid reaches the oral cavity.

7. Diabetes Mellitus

Poorly controlled diabetes is associated with nerve damage (neuropathy) and dry mouth, both of which contribute to BMS.

8. Psychological Factors

Anxiety, depression, chronic stress, and personality disorders are strongly associated with BMS. These factors can alter pain perception and amplify discomfort.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors increase the likelihood of developing Burning Mouth Syndrome, either by directly affecting oral nerve function or by exacerbating systemic imbalances that heighten pain sensitivity:

- Gender: Women, particularly postmenopausal women, are disproportionately affected by BMS. This is believed to be related to hormonal fluctuations—particularly the decline in estrogen—which may alter salivary flow and increase oral mucosal sensitivity. Hormonal imbalances can also influence pain perception and nerve function.

- Age: BMS is more commonly diagnosed in individuals over 50. As people age, there is a natural decline in nerve function and salivary gland activity, both of which can contribute to the symptoms of BMS. Additionally, older adults are more likely to take medications that reduce saliva or affect taste, compounding the problem.

- Chronic Stress or Anxiety: Psychological stress can lead to changes in the way the brain processes pain, increasing sensitivity to oral discomfort. Individuals under chronic stress may also clench or grind their teeth, causing microtrauma that exacerbates symptoms. Anxiety and depression have a well-documented association with chronic pain syndromes like BMS.

- Previous Dental Procedures: Recent changes to oral appliances, tooth restorations, or surgical procedures can sometimes trigger BMS symptoms. The presence of foreign materials in the mouth or subtle nerve trauma during dental work may alter sensory processing in susceptible individuals.

- Polypharmacy: Taking multiple medications, particularly among older adults, is a common contributor to BMS. Many drugs—including antidepressants, antihypertensives, and antihistamines—have side effects like dry mouth or taste alteration, which can mimic or exacerbate BMS.

- Underlying Health Conditions: Systemic illnesses such as thyroid dysfunction, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, or gastrointestinal disorders may disrupt nerve function, hormonal balance, or nutrient absorption. Each of these changes increases vulnerability to BMS, particularly when left untreated or poorly managed.

Diagnostic Approach

Diagnosing Burning Mouth Syndrome is a complex process because there is no single definitive test that confirms the condition. Instead, clinicians must conduct a thorough evaluation and rule out other possible medical, dental, and psychological causes of oral burning. This process is called a diagnosis of exclusion. It is particularly important for patients to understand that the absence of visible lesions or abnormalities does not mean the pain isn’t real—many systemic or neurologic issues can cause oral symptoms that are not outwardly apparent.

A detailed diagnostic workup includes multiple steps:

- Detailed Medical and Dental History: The clinician asks the patient about their symptoms, onset, duration, intensity, and any triggers or relieving factors. They also review past and current medical conditions, recent dental treatments, and all medications being used. This step helps identify potential secondary causes such as diabetes, thyroid disorders, or medication-induced dry mouth.

- Clinical Oral Examination: The mouth is thoroughly examined for signs of infection, trauma, lesions, or allergic reactions. While BMS usually presents without visible changes, it’s crucial to rule out conditions like oral lichen planus, geographic tongue, or fungal infections, which may cause similar symptoms.

- Blood Tests: These are used to detect nutritional deficiencies (vitamin B12, iron, folate), blood sugar levels (to assess for diabetes), and thyroid hormone imbalances. Addressing any deficiencies or systemic diseases can sometimes resolve the burning sensations entirely.

- Allergy Testing: If a contact allergy is suspected—such as sensitivity to dental materials, oral hygiene products, or food additives—patch testing or elimination trials may be conducted. Identifying and avoiding the allergen can lead to symptom improvement.

- Salivary Flow Tests: Measuring the rate and quality of saliva helps assess whether xerostomia (dry mouth) is contributing to the burning. In some cases, imaging of salivary glands may be performed to investigate underlying autoimmune disorders.

- Fungal Cultures or Swabs: Samples from the tongue or other areas may be taken to rule out subclinical candidiasis. Even in the absence of obvious white plaques, a mild fungal infection could be the cause of burning or discomfort.

- Psychological Screening: Since psychological factors like anxiety and depression are strongly linked to BMS, a mental health screening may be recommended. This helps determine if stress, trauma, or other emotional challenges are contributing to symptom severity. Referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist may be advised for comprehensive care.

- Specialist Referral: If initial tests are inconclusive or the condition is particularly persistent, patients may be referred to neurologists, otolaryngologists (ENT specialists), endocrinologists, or oral medicine experts to explore less common systemic or nerve-related causes.

This holistic, patient-centered diagnostic approach ensures that no potential cause is overlooked and that treatment is customized based on the individual’s unique health profile. BMS involves excluding other conditions. There are no specific lab tests for primary BMS, making the diagnosis largely one of exclusion. A full diagnostic approach may include:

Referral to specialists (neurologist, ENT, endocrinologist) may be necessary to rule out systemic causes.

Impact on Quality of Life

BMS can lead to significant psychological distress. Chronic oral pain, even in the absence of visible lesions, may cause frustration, social withdrawal, and feelings of helplessness. Eating and speaking may become difficult, affecting nutrition and communication.

Many patients report being dismissed or misdiagnosed, which can compound their suffering and delay appropriate care. The invisible nature of the condition often leads to feelings of isolation or disbelief from others.

Management and Treatment Options

Management of BMS varies depending on whether the condition is primary or secondary. Treatment goals are to reduce pain, restore oral comfort, and improve quality of life through a personalized approach.

For Primary BMS:

- Neuropathic pain medications: These medications, including clonazepam, gabapentin, amitriptyline, or pregabalin, are often prescribed because they can help reduce nerve-related pain. Clonazepam, in particular, may be used as a dissolvable tablet to be held in the mouth for localized relief. Gabapentin and amitriptyline act on nerve signaling pathways to reduce overactive pain sensations. These drugs require medical supervision due to possible side effects like drowsiness or dizziness.

- Topical treatments: Lidocaine and capsaicin rinses are used directly in the mouth to numb the area or alter nerve pain signaling. Lidocaine provides short-term relief by temporarily numbing the mucosa, while capsaicin works by desensitizing nerve endings through repeated exposure. These treatments are typically reserved for localized or less severe symptoms and may need to be used multiple times daily.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): CBT is particularly effective when anxiety, depression, or chronic stress contribute to the condition. It helps patients develop coping mechanisms for pain, reframe negative thought patterns, and reduce the psychological burden of chronic symptoms. Studies have shown CBT can significantly improve quality of life in chronic pain conditions like BMS.

- Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA): ALA is an antioxidant supplement thought to have neuroprotective effects. It may help by reducing oxidative stress on nerve cells, potentially improving nerve function and reducing pain. While results are mixed, some patients report symptom relief with consistent use under medical guidance.

For Secondary BMS:

- Correct nutritional deficiencies: If blood tests reveal deficiencies in vitamin B12, folate, or iron, supplementation can significantly alleviate symptoms. These nutrients are vital for nerve health and oral tissue maintenance. Treatment may include dietary adjustments, oral supplements, or intramuscular injections for rapid repletion.

- Treat oral infections or candidiasis: If a fungal infection is present, antifungal medications like nystatin or fluconazole are used to eliminate the infection. Once treated, the burning sensation often resolves, confirming the infection as a secondary cause of BMS.

- Adjust or eliminate triggering dental materials: Patients with suspected contact allergies may benefit from replacing dental fillings, dentures, or orthodontic devices with hypoallergenic alternatives. Patch testing may identify specific allergens, allowing for targeted adjustments that ease irritation.

- Address dry mouth: Saliva substitutes like Biotène or sialogogues such as pilocarpine can improve oral moisture and comfort. Patients are also advised to stay well-hydrated, avoid alcohol-based mouthwashes, and possibly use a humidifier at night. Improving salivary flow can greatly reduce burning sensations.

- Control systemic diseases: Managing underlying conditions like diabetes or thyroid disease is crucial. Improved glycemic control, for example, can reduce neuropathic symptoms and help reverse dry mouth. Regular follow-ups with the appropriate medical specialist ensure that systemic health is optimized as part of BMS management.. Treatment goals are to reduce pain, restore oral comfort, and improve quality of life.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

The course of BMS is variable. Some patients experience spontaneous remission, while others may struggle for years with persistent symptoms. Early intervention and a multidisciplinary approach can improve outcomes significantly.

Education and emotional support are critical. Patients must understand that their symptoms are real and valid, even in the absence of visible disease.

Burning Mouth Syndrome is a complex and multifactorial condition that presents significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Its impact on quality of life is profound, yet often underestimated due to the lack of visible pathology. Through thorough evaluation, personalized treatment plans, and continued research, clinicians can better support patients in managing this enigmatic syndrome.

Patients, on the other hand, should feel empowered to seek help, ask questions, and advocate for proper care. With ongoing advances in oral medicine, the future holds promise for better understanding and more effective treatments for BMS.

Keep reading: What Causes Morning Tooth Pain?