Oral lichen planus symptoms, causes and treatment: (OLP) is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects the mucous membranes inside the mouth. It is considered a potentially premalignant disorder, meaning that although it is generally benign, it carries a small risk of developing into oral cancer over time. The condition can be distressing for patients due to its persistent symptoms and impact on daily activities such as eating, speaking, and maintaining oral hygiene. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the symptoms, underlying causes (etiology), and treatment strategies for OLP, targeted at individuals who prioritize their oral health and are seeking in-depth knowledge on complex dental conditions.

What is Oral Lichen Planus?

Oral lichen planus is an immune-mediated mucocutaneous disorder. It primarily affects adults over the age of 40, with a higher prevalence in women. The exact mechanism behind the condition is not fully understood, but it involves a T-cell-mediated autoimmune response directed at basal keratinocytes in the oral mucosa.

OLP can appear on its own or be associated with skin, genital, or nail lichen planus. Although it is not contagious, its chronic nature and potential for malignant transformation necessitate long-term monitoring by dental professionals.

Clinical Symptoms of Oral Lichen Planus

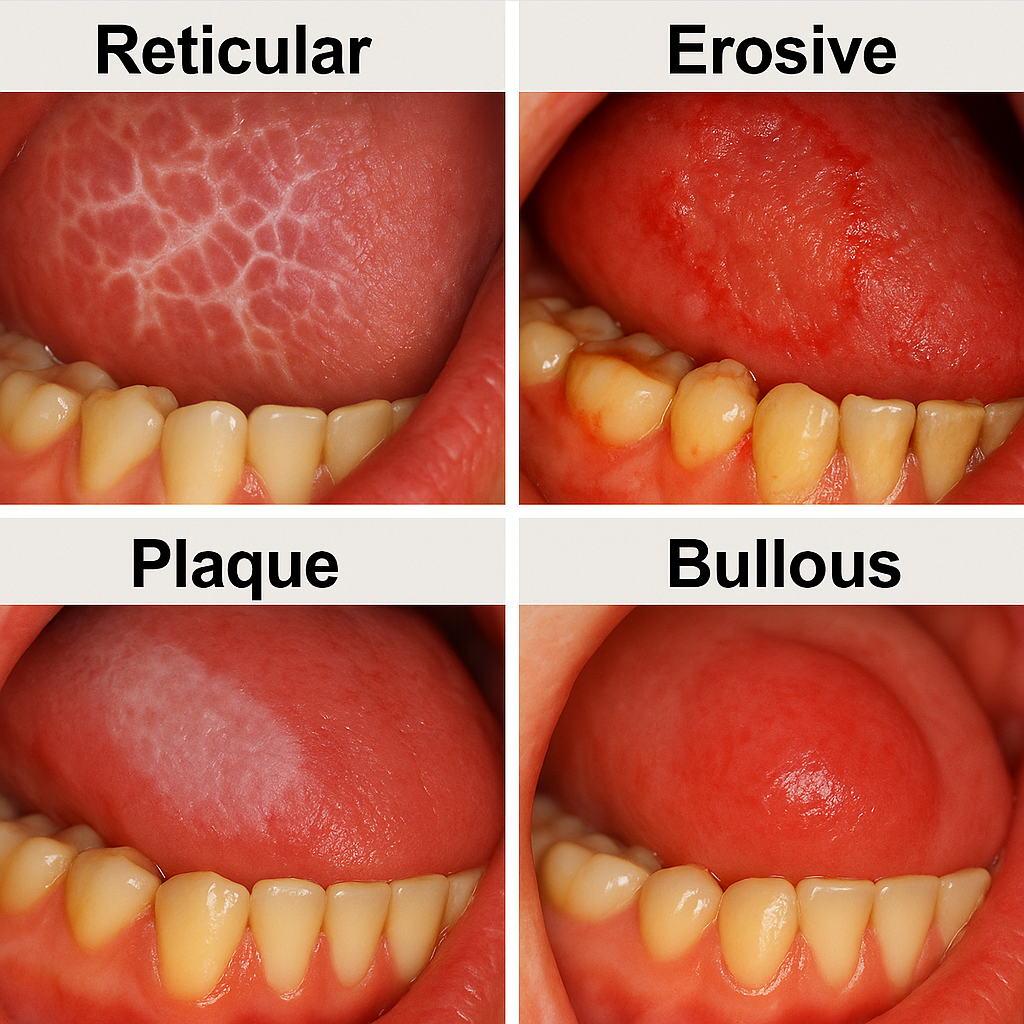

OLP presents in several clinical forms, each with distinct features. The most commonly observed types include:

1. Reticular Form

This is the most common and classic presentation of oral lichen planus. The reticular form is characterized by the presence of Wickham’s striae—fine, white, lace-like lines that intersect across the mucous membranes, primarily on the inner cheeks (buccal mucosa). These lesions often appear bilaterally and are typically asymptomatic, making them a frequent incidental finding during routine dental examinations.

Despite being largely asymptomatic, the presence of these reticular lesions indicates an underlying immune-mediated process. In some cases, mild irritation or dryness may be reported. Because the condition is chronic and lesions may persist for years, patients require monitoring to ensure no progression toward more symptomatic or high-risk forms, such as the erosive variant.

- Characterized by interlacing white lines known as Wickham’s striae.

- Most commonly affects the buccal mucosa (inner cheeks).

- Typically asymptomatic and discovered during routine dental exams.

2. Erosive (Ulcerative) Form

The erosive form of oral lichen planus is more symptomatic and often causes significant discomfort. Patients with this variant experience red, inflamed patches that may evolve into shallow ulcers or erosions. These lesions can be extremely painful, particularly when eating spicy, acidic, or rough-textured foods. Erosive OLP is often associated with gingival involvement, leading to a condition known as desquamative gingivitis.

This form carries a higher risk of malignant transformation compared to other types. Persistent inflammation and epithelial breakdown can predispose the affected areas to dysplasia and, eventually, oral squamous cell carcinoma in rare cases. Regular monitoring, histological evaluation of suspicious lesions, and patient education are essential components of care.

- Features painful red patches, ulcers, or erosions.

- Patients often experience burning or stinging, particularly with spicy or acidic foods.

- This form is associated with a higher risk of malignant transformation.

3. Atrophic Form

Atrophic oral lichen planus is marked by diffuse thinning and reddening of the oral mucosa, typically accompanied by a burning or stinging sensation. These lesions often appear on the buccal mucosa, gingiva, or tongue, and are frequently found in conjunction with reticular or erosive forms. The atrophic appearance results from the loss of epithelial thickness, making the mucosa more susceptible to trauma and secondary infections.

Clinically, this form can be mistaken for other mucosal conditions such as candidiasis or nutritional deficiencies, which necessitates careful differential diagnosis. The discomfort and heightened sensitivity associated with the atrophic form can significantly impact the patient’s oral hygiene habits and dietary intake, requiring a tailored, multidisciplinary management approach.

- Red, inflamed areas with thinning of the mucosa.

- Often overlaps with erosive lesions.

4. Plaque-like Form

The plaque-like variant of OLP appears as homogeneous, well-defined white patches that can resemble leukoplakia, making accurate diagnosis essential to rule out potentially malignant disorders. These plaques most commonly occur on the dorsal tongue or buccal mucosa and are usually asymptomatic. The surface may be smooth or slightly elevated, and lesions may persist for extended periods without noticeable changes.

This form can coexist with other clinical types of OLP and may occasionally exhibit subtle striae at the periphery. Since the appearance closely mimics precancerous lesions, a biopsy is often recommended to confirm diagnosis and exclude dysplasia or carcinoma. Routine follow-up is essential to monitor any changes in lesion morphology or symptomatology.

- Resembles leukoplakia or white patches.

- Usually found on the tongue or buccal mucosa.

5. Bullous Form

The bullous form is the rarest and least stable presentation of oral lichen planus. It is characterized by fluid-filled blisters (bullae) that form under the epithelium. These blisters are typically fragile and rupture easily, leaving behind painful erosive or ulcerated areas. The affected mucosa becomes highly sensitive and may bleed when irritated, making eating and oral hygiene particularly challenging.

Due to its transient nature, the bullous form is often underdiagnosed or confused with other vesiculobullous disorders such as pemphigoid or erythema multiforme. Prompt diagnosis through biopsy and immunofluorescence testing is essential. Management focuses on reducing inflammation, preventing secondary infections, and minimizing trauma to the affected mucosal sites.

- Rare; characterized by fluid-filled blisters that may rupture and cause discomfort.

Commonly affected sites include the buccal mucosa, tongue, gingiva, and lips. Symptoms vary in severity and may range from mild discomfort to severe oral pain that interferes with nutrition and quality of life.

Etiology and Risk Factors

The exact cause of OLP remains unclear, but it is believed to involve an autoimmune mechanism in which cytotoxic T cells target epithelial cells in the oral mucosa. Several contributing factors have been proposed:

- Autoimmune Disorders: Individuals with autoimmune conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, or Sjögren’s syndrome are more likely to develop oral lichen planus. These diseases share common immunological pathways, which may lead to the development of oral mucosal lesions.

- Genetic Predisposition: A family history of lichen planus or other autoimmune disorders may suggest a genetic susceptibility. Although no specific gene has been identified, studies suggest a hereditary link that could increase the risk of immune dysregulation in affected individuals.

- Psychological Stress: Emotional stress, anxiety, and depression can contribute to disease flares or even act as a trigger for disease onset. Chronic stress is known to alter immune function, leading to increased inflammation and impaired tissue repair in susceptible patients.

- Dental Materials: Certain restorative dental materials, particularly amalgam fillings, may provoke a local lichenoid reaction. This is especially true when lesions appear directly adjacent to metal restorations. Patch testing can be useful in identifying material sensitivities.

- Medications: Drug-induced lichenoid reactions can mimic oral lichen planus. Medications like NSAIDs, antihypertensives (e.g., beta-blockers), and antimalarials have been implicated. Discontinuation of the suspected drug may result in lesion resolution.

- Infections: Chronic infections, particularly with hepatitis C virus (HCV), have been strongly associated with OLP in certain geographic regions. The virus may alter immune responses in the oral mucosa, promoting lesion development and persistence.

While OLP itself is not caused by an infection, coexisting infections or systemic inflammation may influence disease expression or severity.

The exact cause of OLP remains unclear, but it is believed to involve an autoimmune mechanism in which cytotoxic T cells target epithelial cells in the oral mucosa. Several contributing factors have been proposed:

- Autoimmune Disorders: Higher prevalence in individuals with lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and other autoimmune diseases.

- Genetic Predisposition: Family history may increase susceptibility.

- Psychological Stress: Stress and anxiety may exacerbate symptoms or trigger flares.

- Dental Materials: Hypersensitivity to amalgam restorations, particularly in lesions adjacent to metal fillings.

- Medications: Certain drugs (e.g., NSAIDs, beta-blockers, antimalarials) may induce lichenoid reactions.

- Infections: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) has been linked to higher rates of OLP in some populations.

While OLP itself is not caused by an infection, coexisting infections or systemic inflammation may influence disease expression or severity.

Diagnostic Approach

For patients experiencing symptoms of oral lichen planus, the diagnostic process can feel both confusing and intimidating. Understanding why specific procedures are recommended helps demystify the experience and promotes patient engagement in their care. Each step is designed to confirm the diagnosis, rule out other serious conditions, and create an effective treatment plan tailored to the individual’s needs.

- Clinical Examination: Dentists start by examining the mouth visually and palpating any suspicious areas. Patients may be asked about symptoms such as burning, pain, or sensitivity. This step is critical for identifying typical lichen planus patterns, like Wickham’s striae, and understanding symptom distribution.

- Biopsy and Histopathology: For patients, a biopsy may seem daunting, but it is a safe, minimally invasive procedure where a small tissue sample is collected under local anesthesia. This sample is examined microscopically to detect characteristic features of OLP, such as degeneration of basal keratinocytes and inflammatory cell infiltration.

- Direct Immunofluorescence: This specialized test may be recommended if the biopsy results are inconclusive or if there is suspicion of similar autoimmune conditions. For the patient, this step involves no extra effort, as the same biopsy sample is often used. The test helps differentiate OLP from diseases like pemphigoid or lupus.

- Exclusion of Malignancy: A critical concern for both patients and clinicians is ruling out oral cancer. Any lesion that looks suspicious, changes shape, or ulcerates over time may need repeat biopsy. Patients are encouraged to attend follow-up appointments regularly to monitor for early signs of transformation.

Understanding these steps not only improves patient cooperation but also builds trust in the care process. Open communication between the patient and dental team ensures comfort and clarity throughout the diagnostic journey.

Diagnosis of OLP typically involves:

- Clinical Examination: Identification of characteristic lesions and distribution.

- Biopsy and Histopathology: Confirmation via microscopic examination showing a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate and degeneration of basal cells.

- Direct Immunofluorescence: Helps differentiate OLP from other mucosal diseases.

- Exclusion of Malignancy: Biopsy is essential if lesions appear atypical or ulcerate.

Differential diagnosis includes leukoplakia, lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, and oral candidiasis.

Treatment and Management

For patients living with oral lichen planus, the goal of treatment is to reduce pain, control flare-ups, and prevent complications such as secondary infections or, in rare cases, malignant transformation. While the condition cannot be cured, understanding the intent behind each treatment helps patients engage actively in their care plan and set realistic expectations.

1. Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are often the first line of defense. These anti-inflammatory medications help reduce swelling, redness, and discomfort at the lesion site. Patients apply them directly to the affected area as a gel, cream, or rinse, typically several times a day. Relief can be felt within a few days, but consistent use is essential to achieve optimal results.

From the patient’s viewpoint, applying the medication may require extra care to avoid spreading it to unaffected areas and ensuring proper adherence. Dentists usually demonstrate application techniques during visits, and patients are advised to avoid eating or drinking for at least 30 minutes after use.

2. Systemic Corticosteroids

For more severe or widespread cases, systemic corticosteroids like prednisone may be prescribed. These are taken orally and work throughout the entire body to calm the immune system’s attack on oral tissues. Patients often notice an improvement within days, but long-term use carries risks such as weight gain, mood swings, and increased infection risk.

Patients should be informed that systemic steroids require careful dosage control and tapering schedules. Regular blood pressure checks, blood sugar monitoring, and physician oversight are also important to manage side effects safely.

3. Calcineurin Inhibitors

When corticosteroids are not effective or cause side effects, medications like tacrolimus or pimecrolimus may be used. These are topical immunosuppressants that block the immune response at a cellular level. For patients, they may come in ointment or gel form and are applied in a similar manner to corticosteroids.

However, patients need to be aware of a potential, though unconfirmed, link to long-term cancer risk. As such, these treatments are usually reserved for stubborn cases and used under close dental and medical supervision.

4. Retinoids and Immunosuppressants

In rare or treatment-resistant cases, oral or topical retinoids—vitamin A derivatives—may be used. Drugs like acitretin help regulate cell turnover and reduce inflammation. Meanwhile, systemic immunosuppressants such as azathioprine are employed to control the immune system more broadly.

Patients prescribed these medications require frequent lab tests and monitoring to ensure liver function, blood counts, and immune markers remain stable. Because of potential side effects, these options are typically introduced only when all other treatments fail.

5. Management of Secondary Infections

Topical steroids can weaken the mucosal defense and predispose patients to fungal infections like oral thrush. When this occurs, antifungal medications, such as nystatin or fluconazole, are prescribed to clear the infection.

Patients should report symptoms like a coated tongue, persistent bad taste, or worsening soreness, as these may signal an underlying infection. Oral hygiene and correct use of medications are crucial to prevent recurrence.

6. Elimination of Triggers

Identifying and removing potential irritants can lead to significant improvement. For example, if a lesion is adjacent to an old amalgam (silver) filling, replacing the material may resolve inflammation. Likewise, switching medications that cause lichenoid reactions can reduce flare-ups.

Patients should share a detailed health and dental history with their care providers and alert them to any changes in medications. Allergy testing may also help uncover previously unknown sensitivities.

7. Stress Reduction and Psychosocial Support

Stress is a known trigger for many autoimmune conditions, including OLP. For this reason, stress-reduction strategies such as mindfulness, therapy, exercise, or even lifestyle counseling can be incredibly beneficial.

Patients are encouraged to track emotional and physical symptoms to identify stress-related patterns. A supportive care team may include not just dentists, but psychologists or counselors familiar with chronic illness coping strategies.

8. Regular Monitoring

Because oral lichen planus can persist for years and has a small risk of developing into oral cancer, regular monitoring is essential. Dentists typically recommend follow-up visits every 3 to 6 months.

At these visits, changes in lesion appearance are documented, and any ulcerated or suspicious area is biopsied to rule out malignancy. Patients should inform their provider of any new pain, bleeding, or lesion growth between visits to ensure early intervention.

There is no definitive cure for OLP, and treatment is aimed at controlling symptoms, reducing inflammation, and preventing complications.

Summary

1. Topical Corticosteroids

- First-line treatment for symptomatic cases.

- Common agents include clobetasol propionate and fluocinonide.

- Applied as gels or rinses to affected areas.

2. Systemic Corticosteroids

- Reserved for severe, widespread, or refractory cases.

- Requires careful monitoring due to side effects.

3. Calcineurin Inhibitors

- Agents such as tacrolimus or pimecrolimus may be used in steroid-resistant cases.

- Potential risk of carcinogenicity necessitates long-term surveillance.

4. Retinoids and Immunosuppressants

- Oral or topical retinoids (e.g., acitretin) may be beneficial.

- Immunosuppressive drugs like azathioprine are considered in extreme cases.

5. Management of Secondary Infections

- Antifungal agents may be required to address secondary candidiasis from steroid use.

6. Elimination of Triggers

- Replacement of dental amalgam with biocompatible materials in hypersensitive patients.

- Review and modification of systemic medications if drug-induced lichenoid reaction is suspected.

7. Stress Reduction and Psychosocial Support

- Stress management techniques and mental health support may improve symptom control.

8. Regular Monitoring

- Biannual check-ups to monitor lesion progression.

- Biopsy any lesion that changes in appearance or ulcerates.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

Most cases of OLP are chronic and recurrent. While some patients may go into remission, others experience periodic flares. The erosive and atrophic forms require close monitoring due to the increased risk of malignant transformation, estimated to be around 1-2% over time.

Patient education is vital to ensure adherence to treatment plans and prompt reporting of new or worsening symptoms. With appropriate management and regular dental follow-up, most individuals can maintain good oral function and quality of life.

Related: How Rheumatoid Arthritis Affects Oral Health

Oral lichen planus is a complex, multifactorial condition that demands a personalized and multidisciplinary approach. Though there is no cure, effective symptom control is achievable through topical and systemic therapies, trigger avoidance, and vigilant monitoring. Empowering patients with knowledge and timely access to care plays a critical role in preventing complications and enhancing overall oral health outcomes.